Can the practice of law be reduced to a checklist?

Time and time again we hear that there is ‘no room for error’ in the practise of the law.

Lawyers trade on finding ways to mitigate risk for their clients. But can they be fallible themselves?!

Of course they can. Yet, in some industries, error can literally mean life or death.

What can the legal profession learn from these industries, and can lawyers find new ways to squeeze more risk from their work?

Working with Lupl, LexisNexis sat down with a carefully selected group of partners, associates and in-house counsel from around the world to find out.

Countering complexity with checklists

In the New York Times bestseller, The Checklist Manifesto, Atul Gawande argues that the work of professionals has become so complex, even the best can no longer depend on memory or intuition alone to get things right every time.

The solution to all this complexity, according to Gawande, is radically simple - a checklist. Checklists are written sets of tasks that professionals can use to make sure they are doing the right things, in the right order, every time. Without checklists, he argues, things take longer, steps get missed, and outcomes are worse. He backs it up with data from studies all over the world.

Gawande is a surgeon – but he argues that the need for checklists applies equally to pilots, dentists, construction workers and accountants.

But what about lawyers? In a knowledge industry like law, where every M&A deal, every employment litigation, and every regulatory matter, is different – and the top partners are celebrated for their unique expertise and experience – do checklists have a role to play? And, even if they do, are lawyers ready to embrace them?

“The volume and complexity of what we know has exceeded our individual ability to deliver its benefits correctly, safely, or reliably.”

Atul Gawande, The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right

A brief history of checklists in the legal profession

For as long as lawyers have been practising law, they have been making lists of things to do, steps to follow, and issues to address.

Law firms have traditionally used checklists in various forms to manage their workflow, particularly in areas with complex and repetitive tasks such as litigation, due diligence, compliance, and residential conveyancing.

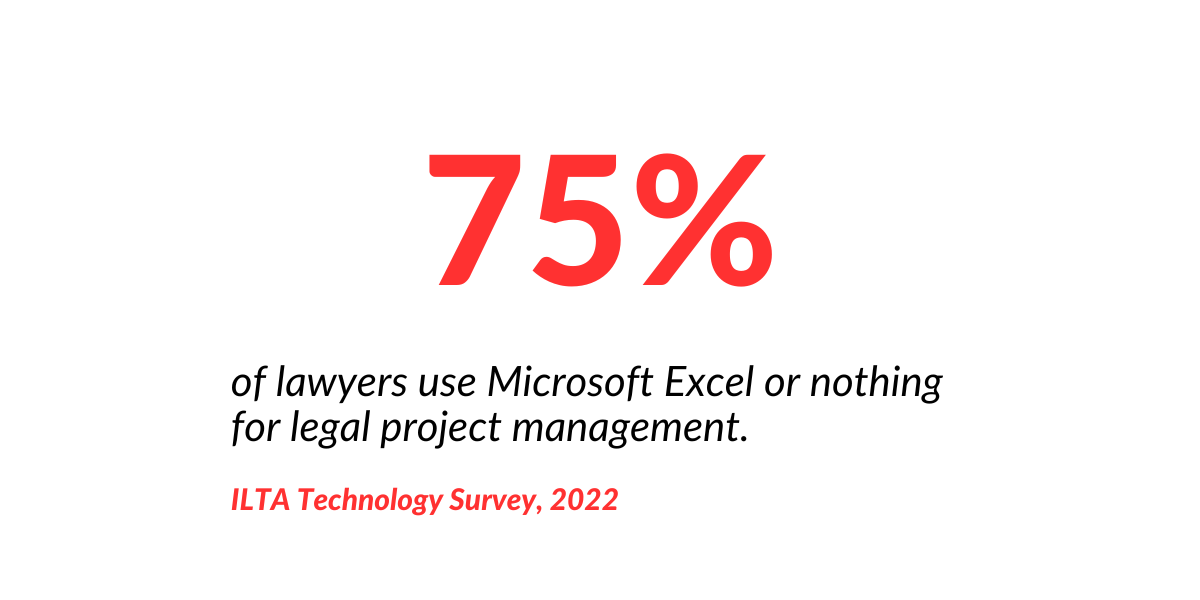

Today, these checklists are often embedded in Word documents, Excel tables, emails, or in notepads.

Sometimes, individual lawyers have their own checklists. More rarely, they exist at the department level. And more rarely still, checklists are rolled out at a firm-wide level to embed a consistent way of doing things.

6 things we learned about lawyers and checklists

After interviewing 30 carefully selected partners, associates and in-house counsel in the UK, US and Singapore, the team at Lupl and LexisNexis uncovered six common themes.

1) There are two types of checklists in the law – and one is far more common than the other

From our conversations with lawyers, it became clear that two types of checklists exist in the practice of the law.

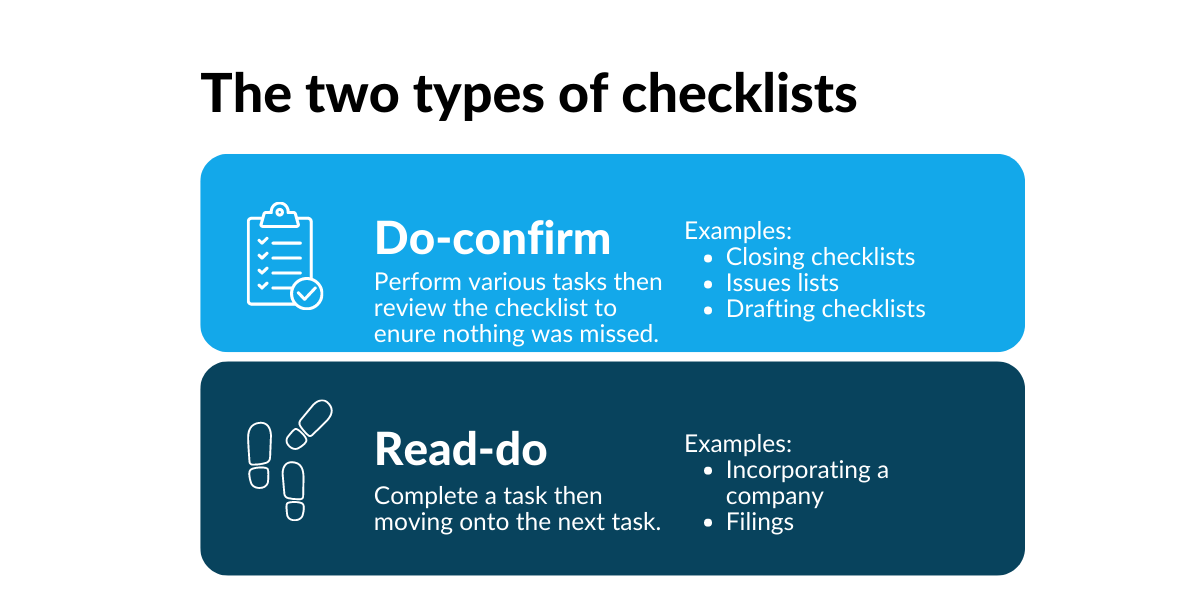

The first aligns with what Gawande calls “Do-Confirm”. In a Do-Confirm checklist, you perform the various tasks – and then you review the checklist to make sure nothing got missed.

Closing checklists are one example of Do-Confirm checklists – the parties on a transaction finalise the various closing items and regularly review the checklist to make sure everything is completed. Another example is a drafting checklist – where a lawyer drafts a document and then reviews the checklist to make sure all the key issues are addressed.

In contrast, “Read-Do” checklists are more like recipes. You read a step, then you do that step, then you move onto the next step, and so on. An example would be a company incorporation checklist – a process-driven flow where certain steps must be performed sequentially.

Our research found that Do-Confirm checklists are much more common than Read-Do checklists in the legal sector.

2) Lawyers see significant value in checklists

Unsurprisingly, our research aligned with the findings from Gawande's book – just like the other professions covered in his research, lawyers consider checklists to be important – and increasingly so.

The lawyers we spoke with shared stories of feeling overwhelmed by their workloads and the range of tasks they needed to complete and track every day, highlighting how checklists can play a part in keeping things on track and under control. This aligns with findings from LexisNexis' Bellwether 2023 survey, which revealed 75% of lawyers from small and solo practices in the UK believe keeping up to date with changes in the legal industry and law is a challenge.

Here are some of the other benefits of checklists shared by the lawyers we spoke with:

Benefits of checklists according to lawyers

|

Benefits |

Examples |

|

Practice law in the firm’s unique way |

Templates or playbooks for handling different types of matters |

|

Manage risk |

Make sure the team doesn’t miss an important step in a process; manage decision fatigue |

|

Increase speed and efficiency |

Hit the ground running; avoid reinventing the wheel. |

|

Get a better first draft |

For more senior lawyers, leveraging checklists to allow more junior lawyers to prepare a first draft of a document or process plan |

|

Create shared understanding |

A shared checklist can engender a shared understanding of what needs to be done and by when – and who is doing it |

|

Onboard new team members faster |

Several lawyers reported that checklists helped them when they joined new teams in understanding what needed to be done and the current status of tasks |

|

Improve quality |

There was general agreement that, when used properly, checklists generate better outcomes |

|

Improve client service |

Lawyers felt that with a checklist they could present a clear journey for the client through the matter |

One might conclude that, based on these findings, we also learned that lawyers, like pilots or surgeons, have checklists embedded in every aspect of their working day. Well, not quite…

Despite sharing all the benefits they saw in checklists, the lawyers we spoke with also reported blockers to using them more widely in their work.

3) Lawyers object to being told their work is repeatable

Several of the lawyers we interviewed expressed the belief that, while checklists might serve others well, the unique nature of their own cases would make a checklist harder to implement.

They suggested that their work's distinctive intricacies could not easily be streamlined or simplified into a standard checklist without risking oversimplification or overlooking key details.

This was an interesting finding, particularly when mapped against Gawande’s research. If checklists can be used to undertake brain surgery or land a plane in difficult conditions, it does beg the question - why can’t they be used in M&A or real estate matters?

Just look at the potential use cases that come alongside generative AI tools. A LexisNexis survey of 1,000+ lawyers in the UK found a strong appetite to use generative AI tools for researching matters, briefing documents, document analysis, due diligence and business development activity - all of which would be carried out by AI as opposed to lawyers.

Interestingly, the lawyers who raised this objection tended to conceptualise checklists as being more like a Read-Do “recipe” with rigid steps, rather than a flexible Do-Review plan, implying that part of the challenge lies in the understanding that checklists come in multiple forms and can be used in multiple ways.

4) Lawyers object to up-front work required to build checklists

This was a big one. Despite agreement on the overwhelming benefits of checklists, most of the lawyers we spoke with flagged the effort that goes into building them.

Lawyers are, of course, busy people – with client deadlines and billable hour targets to meet. They were united that they would build and use checklists a lot more if there could be a more effortless way to create, share and modify them – perhaps based on previous matters.

5) Checklists today are clunky and difficult to collaborate on

When asked for an example “checklist”, most of the lawyers we spoke with reached straight for Microsoft Word, pulling up a table view in a document. For transactional lawyers, it was closing checklists, steps plans or issues lists. For disputes lawyers, it was pre-trial litigation activities.

There was a lot the lawyers liked about Word checklists. They reported finding them easy to use (not least because much of their working day was already spent in Word) – and were reassured that as every lawyer on earth can open a .DOC or .DOCX, there would be no access or familiarity issues for recipients.

But every single lawyer using Word checklists spent even more time venting various frustrations:

- Out-of-date the moment they are sent

- Difficult to sort, filter and organise information

- Highly manual to manage and maintain

- Absence of collaborative editing means endless trading of checklist versions via email

6) Checklists today are not easily actionable

Finally, many of the lawyers found that checklists were not easily actionable in the context of the matter at hand.

For example, an employment lawyer pointed out that she believed it was helpful to be reminded in a checklist document that an important early step in a pre-trial checklist is to identify defects in the complaint or demand.

But she also felt that this task warrants a checklist on its own. Additional work is required to put this knowledge to work – specifically, writing an email or sending a message to an associate to undertake the review, setting a deadline, following up to make sure the task is completed, reviewing the output, and so on.

What's the solution?

There can be few other aspects of law firm operations with such a clear disparity between the recognised value of a solution and the actual adoption of that solution in daily legal practise.

After listening to these conversations with lawyers, the product & UX teams at LexisNexis and Lupl got together and came up with some interesting potential solutions.

The team quickly zoomed in on the concept of matter templates or playbooks – prebuilt legal matters, or component parts of legal matters, embodying all of the tasks, steps, documents and resources a lawyer needs to plan, organise and deliver a given legal matter or workstream.

1) Established industry content

Building an initial library of checklists based on LexisNexis’ vast content library provided reassurance to lawyers that they would be following the right steps in the right order.

2) Suggest rather than require

Knowing that lawyers object to any sense of their matters being put “on rails”, the design for the templates ensured that the lawyers have a choice at each stage of the process – from initial creation of matters through to managing tasks inside of a matter.

3) Make the checklist actionable

Integrating the checklist into the LPMs lawyers use means that tasks can be assigned to team members, priorities and deadlines can be set, and reminders can be sent automatically. In short, the checklists started to come to life as soon as they were implemented.

4) Fully flexible, fully editable

Overcoming the sense that “checklists don’t work because every matter is different” was key to the design. Once a checklist was pulled into a matter, we designed the feature so that every aspect of the checklist is editable based on the unique needs of the case.

5) Available at the point of need

In the same way as pilots have a checklist for take-off and a separate checklist for dealing with mechanical failure, lawyers reported needing the ability to pull in checklists as the needs of their matter evolve. The solution was therefore designed to ensure that checklists could be used at matter creation or in a modular way during the life of a matter. For example, if a matter starts off being non-contentious (a transactional re-negotiation, perhaps) but evolves into a contentious matter, lawyers would be able to bring in relevant checklists for each part of the case.

6) Easy to save and create new templates

Last, but by no means least, was the need to overcome “checklist inertia” – the initial effort going into building checklists. First, by pre-seeding the library with 50+ LexisNexis checklists based on common work types, the platform provided a great starting point for many matter types. And second, the feature was designed so that lawyers can save their existing matters right back into the template library, taking all the effort out of template creation.

Conclusions

In the end, like most things in legal tech, change is about more than just implementing a tool – it is also about transforming attitudes.

The incorporation of checklists into legal practise is not an implication that a lawyer's expertise is somehow insufficient or less valuable. Rather, it acknowledges the inherent complexity of legal work and the human tendency to overlook or forget things. A checklist serves as a safety net, catching anything that might otherwise slip through the cracks.

Checklists exist widely in our profession – but the challenges we uncovered in this research have certainly prevented them being more deeply integrated into working practises in the way we’ve seen in other industries.

If technology-driven solutions like the templates and playbooks developed by LexisNexis and Lupl can overcome these challenges, maybe Gawande will be proven right – and lawyers will join surgeons and pilots in celebrating, rather than resisting, the use of templates in their daily work.

See the checklists in action

To view our checklists, get a demo here.