The LexisNexis Legal Aid Deserts report

LexisNexis pinpoints the locations across England & Wales with the highest need for legal aid providers and the least access to them.

Having access to legal advice - regardless of how much you earn, where you live or how freely you can travel - is fundamental to upholding the Rule of Law.

Legal aid should act as a safety net to ensure people can access and protect their rights.

That’s why LexisNexis decided to investigate the geographic locations that are most in need of legal aid support but have the least access to it.

Legal aid is fundamental to upholding the Rule of Law

Millions of us are reliant on a legal aid system that is chronically underfunded and understaffed – and it has been getting noticeably worse for years.

This challenge is exacerbated for people living in remote or rural areas, where legal aid providers are few and far between.

At LexisNexis, the Rule of Law plays a central role in our purpose as an organisation – and providing people with access to legal representation, regardless of where they live or how much they earn, is fundamental to upholding the Rule of Law.

This report highlights the millions of people throughout the UK who live in legal aid deserts with limited or no access to legal aid providers.

The aim is not to place blame. Instead, we want to drive the conversation about how we, as a legal community and as a society more broadly, can better support our country’s most vulnerable people.

James Harper, Director, Global Legal at LexisNexis

Identifying legal aid deserts

A quick run-through of the methodology used to identify legal aid deserts throughout the UK

There's no easy way to define exactly what a legal aid desert is; nor is there only one way of viewing it. But for simplicity's sake, we have designed our own metric by comparing supply with demand in each local authority, and then characterising legal aid deserts as the local authorities at the bottom 10% of that metric. This is not the sole problem, and nor does this mean that provisioning in areas outside this metric is “good”. On the contrary, there are many areas of challenge. However, to drive the conversation, it is important to identify the areas of greatest need.

Using publicly available government data, this report compares legal need against legal aid supply to highlight the country's legal aid deserts.

We focused on the following areas of the law:

Legal need was determined by the number of legal "incidents" in a local authority area (for example, domestic abuse cases, homelessness or crimes committed), while legal aid supply was determined by using the number of legal aid providers in a local authority area as a proxy.

We then calculated legal need and supply per 10k people to make local authorities with different population densities comparable. When calculating the the need and supply of the local authorities, we also took into consideration the need and supply of neighbouring local authorities. We did this by measuring 15km from the centre point of a local authority to the centre point of a neighbouring local authority. For the sake of simplicity, our calculations ignore need and supply might be split between two different neighbouring local authorities that are not neighbours.

We then assigned a final metric to each local authority by dividing supply by need. The local authorities in the bottom 10% of that metric were given the title of legal aid desert.

It's worth noting that we were only able to work with the data available to us – a lack of data for many local authorities meant we had to make several other assumptions. Although we believe the impact of these assumptions to be insignificant, it's worth highlighting yet again the primary objective of the below maps is to raise awareness about the lack of access so many people throughout England and Wales have to the current legal aid system.

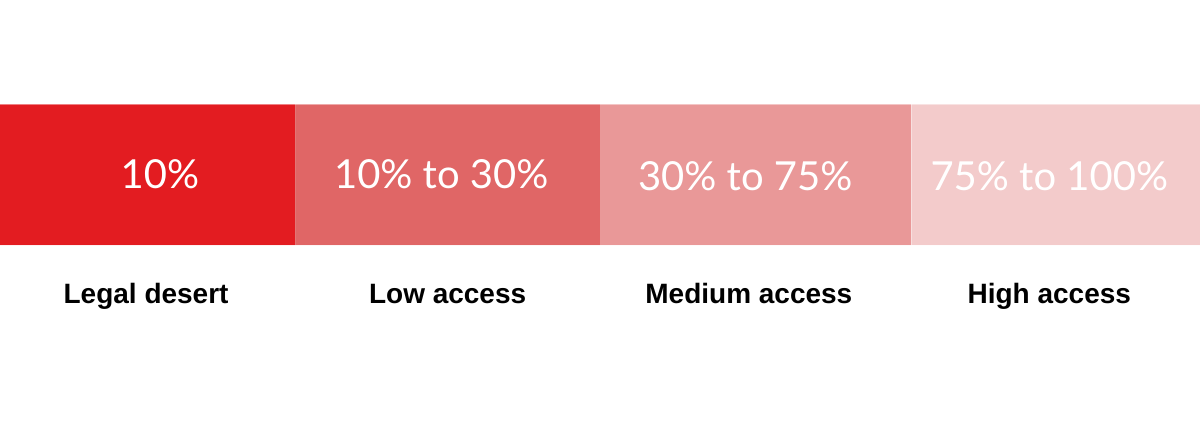

Legal aid desert percentage brackets

We characterised local authorities in the bottom 10% of the metric as being a legal aid desert.

Housing legal aid deserts

The research revealed:

- 12.45m people live in legal aid deserts for housing

- The five best served local authorities have 1.74 providers per 1,000 incidents

- The housing legal deserts in the bottom 10% had 0 providers per 1,000 incidents.

To measure the need for housing legal aid throughout the country, we looked at a number of metrics, including social housing waitlists, evictions and homelessness.

Our data highlighted that there are many housing legal aid deserts throughout the country and only a few areas with medium to high supply.

Our analysis of the data pinpoints the following 15 locations that have a high legal aid demand but no or limited access to legal aid support.

Top 15 legal aid deserts for housing:

1) Stratford-on-Avon

2) South Lakeland

3) Boston

4) Bassetlaw

5) East Devon

6) Wyre Forest

7) Isles of Scilly

8) North Norfolk

9) North Devon

10) Forest of Dean

11) Wychavon

12) Somerset West and Taunton

13) Doncaster

14) Barrow-in-Furness

15) Cheshire West and Chester

Regions with the most legal aid deserts for housing:

East of England (22)

South East (22)

South West (15)

East Midlands (10)

West Midlands (10)

Halsbury's Laws of England on Social Housing - get info and practical guidance

Jasmine Basran, Head of Policy and Campaigns at Crisis, says:

"Access to justice is a fundamental right that should be available to everyone in our society. Legal aid plays a significant role in this for people on low incomes where cost can be a barrier to justice. This is especially true for people who are homeless, experience the sharpest end of poverty and can face economic barriers and social stigma, which reduces the likelihood of being able to access justice."

View the latest Property Law practice notes, legislation, precedents and more.

Family legal aid deserts

The research revealed:

- 1.09m people live in legal aid deserts for family

- The five best served local authorities have 14.43 providers per 1,000 incidents

- The family legal deserts in the bottom 10% had 0 providers per 1,000 incidents.

Demand for family work escalated during the COVID-19 pandemic, creating more work than barristers and solicitors could get through. This increase in demand also placed a huge strain on the Family Courts, with many turning to virtual channels to make their way through a growing backlog of proceedings.

The data we gathered identifies some areas with a worryingly high demand for legal aid services and little or no local representation.

Find out more about eligibility for family legal aid

Moreover, it's worth noting that we anticipate the real numbers to be considerably higher. Unlike housing, which is highly-publicised and more likely to be reported, family law incidents often go by undetected. In addition, our research only captures public cases - if we were to add data of private cases, we believe there would be a noticeable change in the numbers and maps (with more areas showing as under-supplied).

Meanings of 'family mediation' and 'help with family mediation'.

It's also worth noting that incidents for domestic abuse were determined by the police force area (PFA) as opposed to local authority - we applied this based on their population.

Our research highlighted a number of legal aid deserts for family law - below are 15 locations with high family legal aid demand but no or limited access to legal aid services. Interestingly, many of these deserts are located in the South East, going against the stereotype that legal aid deserts only exist in the north or central parts of the country.

Top 15 legal aid deserts for family:

1) Wychavon

2) Derbyshire Dales

3) East Cambridgeshire

4) Ribble Valley

5) North Norfolk

6) Isles of Scilly

7) South Hams

8) West Devon

9) Rutland

10) Wealden

11) South Holland

12) Melton

13) Craven

14) Selby

15) Mid Sussex

Regions with the most legal aid deserts for family:

East Midlands (4)

South West (3)

East of England (2)

Yorkshire and The Humber (2)

Family law barrister at Goldsmith Chambers, Shárin Diegan, says:

“Having an understanding of legal aid deserts – where they exist and where the problems are – is so important to how we address the imbalance and ensure everyone has access to good legal advice in the future.”

Law Society of England and Wales President, Lubna Shuja, says:

“We know many people across the country, who are on low incomes, are facing serious legal problems – such as those about to lose their homes or those fleeing domestic violence. They are unable to get access to the advice they are legally entitled to."

Homelessness reviews and strategies

But the picture for cases involving a family breakdown, such as divorce and child contact, is likely to be even worse than the maps suggest, says Shuja.

“There will be family legal aid providers shown in the maps who are only providing legal aid for cases related to children in care. This means for those fleeing domestic violence, who want to resolve relationship breakdown or child contact issues, access to legal advice is more sparce.”

Almost three quarters (71%) of respondents to a Rights of Women survey said it was either difficult or very difficult to find a legal aid solicitor in their area. A third of respondents (33%) were having to travel between five and 15 miles to find a legal aid solicitor, and 23% had to travel more than 15 miles.

The number of providers has reduced even further, says Shuja. "Over the last decade, the number of family legal aid firms has more than halved. From July 2021 to July 2022 alone, another 83 family legal aid offices closed down, along with 32 housing legal aid offices and 68 crime legal aid offices."

v

Crime legal aid deserts

The research revealed:

- 2.12m people live in legal aid deserts for crime

- There are only 0.89 providers per 1,000 incidents in the five best served local authorities

- The crime legal deserts in the bottom 10% had 0 providers per 1,000 incidents.

Legal aid relating to the criminal justice system has been in the spotlight recently, with thousands of barristers striking over pay.

View proceeds of crime

The gaps in our justice system have become painstakingly clear in recent years through the news coverage of this strike and, in recent years, by various mainstream books detailing the reality of the issues we face – including those published by The Secret Barrister.

However, these gaps have been in existence for a long time - and for those living in legal aid deserts, they can be near impossible to cross.

Read Halsbury's Laws of England on the justice system and children

Criminal legal aid was calculated by assigning the number of incidents in a police force area (PFA) to the different local authorities based on their population.

Top 15 legal aid deserts for crime:

1) Swale

2) Tunbridge Wells

3) Ribble Valley

4) Rutland

5) Mendip

6) East Hampshire

7) Test Valley

8) East Cambridgeshire

9) Huntingdonshire

10) Derbyshire Dales

11) North Norfolk

12) Copeland

13) Babergh

14) Horsham

15) Cotswold

Regions with the most legal aid deserts for crime:

South West (8)

South East (5)

East of England (4)

University of Manchester Legal Advice Centre (LAC) manager and practicing criminal defence solicitor, Fintan Walker, says:

"The strain on the legal aid system is becoming more noticeable. The number of firms relinquishing their legal aid contacts, predominantly criminal, has risen, even in large and highly populated areas such as Greater Manchester. Firms that are continuing to provide a legally aided service are struggling to recruit young lawyers due to noncompetitive salaries. This has led to more pressure on the pro bono sector to fill the gaps."

View LexisNexis' Corporate Crime legal library and guidance here.

Legal aid deserts overall map

By combining data across all three branches of the law with the data from local authorities, we were able to pinpoint the following overall legal aid deserts.

Overall legal aid deserts in the UK:

1) North Norfolk

2) Derbyshire Dales

3) Isles of Scilly

4) Ribble Valley

5) East Cambridgeshire

6) West Devon

7) Rutland

This is useful at highlighting the areas with the highest and lowest access to legal aid across all three areas of the law. The local authority areas with low or no access to legal aid across housing, family and crime hint at an overwhelmingly low access to legal aid.

As noted above, we appreciate that the three areas we have studied – family, housing and crime – are not the only areas of importance. However, we are confident that this data can serve as an accurate proxy from which to make assumptions across broader legal aid provision.

Working towards a better legal aid system

As with all major challenges facing our society, legal aid is a complex and heavily-debated issue, with layers of intricacies that need to be taken into consideration. Identifying an appropriate solution, therefore, is no small feat.

However, what is certain is that legal aid has been consistently cut for some time, to the point where very few people in very few types of cases now qualify as being able to receive it, says LexisNexis' Director of Global Legal, James Harper.

One non-profit that takes on hundreds of cases every year is the Free Representation Unit (FRU) - although its CEO, David Abbott, says there are tens of thousands of people who still can't access justice.

"This work by LexisNexis is an important contribution to an objective description of the scale of unmet legal need in England and Wales. Each day FRU receives calls from these and other areas where there is no local source of legal help and we can't help."

But early legal advice can not only reduce personal stress, it actually saves the economy money, says Abbott.

"The lack of access to early legal advice is demonstrated when the FRU represents clients in legal hearings. Litigants in person make incorrect applications whilst other legitimate claims have been missed. This slows down the court process and prevents clients from accessing justice."

According to a report by the World Bank Group, every £1 invested in legal aid will give you a greater return. For instance, housing advice has the potential to save the state £2.34, while debt advice can save £2.98, employment advice can save £7.13, and social welfare entitlements can save £8.80.

One of the biggest challenges facing the legal aid system is money, says Rebecca Wilkinson, CEO of solicitor pro bono charity LawWorks.

"When you want a robust system that works for everyone geographically, it costs money. But in the same way, we've funded an expensive health care system because we think it's an important part of our society, so too should we be investing in our legal aid system."

However, Wilkinson was quick to point out that legal aid requires a high-volume of administrative work, which easily eats up funding.

"It's not simply the costs of legal aid representatives, it's the significant amount of admin work that goes into it. Obviously, we want government money to be spent efficiently and appropriately and for there to be a good audit, but equally, we are talking about the most vulnerable people in our communities."

It's for this reason that LawWorks has delivered a number of projects designed to reduce the administrative burden placed on legal aid by providing support, says Wilkinson.

Besides better funding for the legal aid system, another way to provide additional ad-hoc support is through pro-bono work.

Harper believes lawyers have a duty to use their rare set of skills to make a difference for people that would have no other ability to access those skills.

"The things that are so easy for a lawyer to do, those skills which are just innate, are so incredibly valuable and out of reach to many people. For example, the ability to look through a bundle of paperwork and make some sense of it without feeling overwhelmed – that is a skill which is natural for a lawyer but alien to so many in society. It is something I have done when volunteering in free legal advice clinics – I may have had no expert knowledge of the relevant law, but I can sort through stuff and bring sense where there’s lots of words and numbers. I believe that I owe it to people to use my skills to make a difference."

Wilkinson says she's seen a growing awareness in the legal community of the impact pro bono work can have.

"Most of the lawyers we work with are commercial lawyers. They have the skillset because of their training and their knowledge of the legal system to really help people who can't access legal support."

"If you've got these skills, let's find a way to hone it and utilise it," she says, pointing out that the purpose of organisations such as LawWorks is to help facilitate.

"Just half an hour of a solicitor's time can make a huge difference to people's lives."

Harper reflects that this can only be part of the solution, however.

“The answer cannot sit just with lawyers giving up time pro bono – pro bono cannot be a replacement for a properly funded legal aid system. It might be a start but, in order for our economy to flourish, for our society to prosper, and for the Rule of Law to be protected, respected and advanced, far more needs to be done. We need to address the systemic challenges which means access to justice is often denied to people across the country, almost always at the darkest moment of their lives”.